Beethoven’s Symphony No.1 in C tellingly takes a cue from Mozart’s last symphony also in the same key. Alexander Soddy and BSO’s on-point performance comprehensively registered Beethoven’s compliment to the genre in the 18th century as well as signposting its pivotal development forging forward into the 19th. The composer’s confidence of form and innovation were conveyed throughout with a teasing combination of Classical style merged with propulsive tempi and clarity of textures brimming with humour and orchestral virtuosity. This was Beethoven springing from the starting blocks as the great driving force on the great symphonic road ahead.

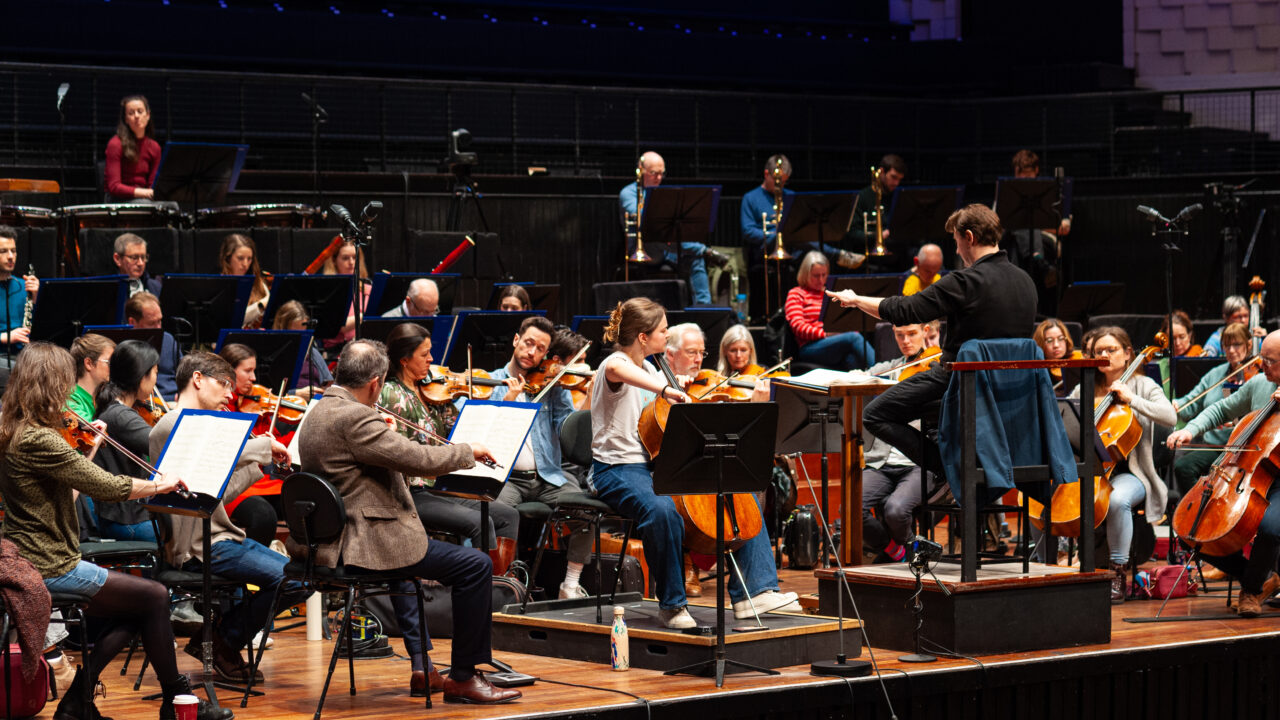

From the Beethovenian birth of new genius looking to the future, Elgar’s Cello Concerto followed in sharp contrast to take us over the bridge into past experience and disillusion. The spirit of Jacqueline du Pré may still haunt the work, but as with all great masterpieces, myriad ways of individual expression can realise the personae and temperaments pictured within. Soloist Laura van der Heijden, an outstanding previous BBC Young Musician, drew Elgar’s characters and moods with compelling conviction and the broadest range of expressive nuance, all with zero self-regard. Palpably inhabiting the work from within, she communed with every section or soloist in the orchestra to reveal the composer’s journey of withdrawal from the personal and public light of life into darkest isolation.

If Elgar didn’t ever explore coastal northern England, he may have missed a trick. The encore brought a surprisingly apt and inclusive stroke of insight. Audience, conductor and orchestra were invited to hum a drone on a low G, while cellist Laura sang and accompanied herself in the song Scarborough Fair. The repeated lyrics Remember me to one who lives there – She once was a true love of mine opened another relevant and personal Elgarian box almost as much as the concerto we had just heard. Go figure…

In 1890 the 25 year-old Richard Strauss created a roaring pair of innovative tone poems that could be seen to develop from Liszt what Beethoven took from Mozart. Composed consecutively and both ground-breaking early in his career, Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration mirror life and death, but in stark contrast. The latter is notably more personal rather than merely theatrical, to the extent that when the composer himself was dying post-WW2 in 1949, he reflected on how his music matched the reality of his own final days.

Strauss could often be his own worst enemy and D&T performances can readily divide into showpiece or sincerity mode – wholly understandable when the subject matter is so richly emotional and spectacularly orchestrated. Finding the right balance in performance is crucial and for me, this one consistently hit the target with spectacle, but fell a tad short on sincerity. Audience response spoke otherwise, so I readily defer to being in the category of one man’s meat or poison. That said, the closing Transfiguration raised the roof to magnificent heights of hope and glory – job done.

Once again, special mention for the BSO’s Digital Concert presentation, which compliments the live experience at home with great sound and camera work. Catherine Bott’s contribution on the music and performers was the ideal introduction to content, and the interval film on the Bristol Recovery Orchestra highlighted the amazing regional community work of BSO out and about.

Critic Ian Julier

If you missed the concert you can catch up until 15 March here

Gallery